REALWHISTORYWW.COM – Just as modern indo-caucasian and roman-paulinian1 culture is far removed from ancient hebraic, unitarian – and black israelite – culture , so too is modern Arab culture far removed from original arab – black ismaelite – culture – it is now Turkish culture. During the time of the Turkish Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1922), Islam was not known as the Arab religion, it was known as the Turkish religion. The parallel between these two shifts from original black cultures carrying authentic prophetic messages to adulterated indo-caucasian versions is striking. This is most interesting when observing how in this adulteration process a strong anti-black culture inherited from the ancient ideology of the hindu jinn – or hyperterrestrial creature also often referred to as a devil – venerated as Indra (and his “Rig Veda”) in India developed considerably but perniciously within those indo-caucasian communities that still claimed or wanted to retain the black ismaelite or israelite spiritual and prophetic heritage!.. Indraism (which is rejection at the political, social and economic level of Blacks but also rejection at the hyperpolitical level of the black ismaelite and israelite Prophets of Divine Revelation ) inspired the nazis in Germany and still inspires strongly ashkenazi “Eretz Khazaria” ethnic suprematism, neo-conservatism or anglo-american ethnic suprematism masquerading as “exceptionalism” in US, india’s powerful apartheid and anti black system; Al Turki’s and Al Seoud’s “Arabia” discrimination system against blacks (even against the authentic and true arabs that are black). Indraism is the transversal and unifying matrix of all these systems, the true proto-nazism that still strongly permeates all indo-caucasian cultures in the world especially in Europe, India, “Seoudi Arabia” and America.

Over a hundred million people in the world call themselves Arabs. That is to say the least, a potential force in world politics, quite apart from the question of oil. Yet many observers are inclined to doubt whether there is any reality underlying the common use of the term Arab. And it is indeed not easy to define what is meant by an Arab.

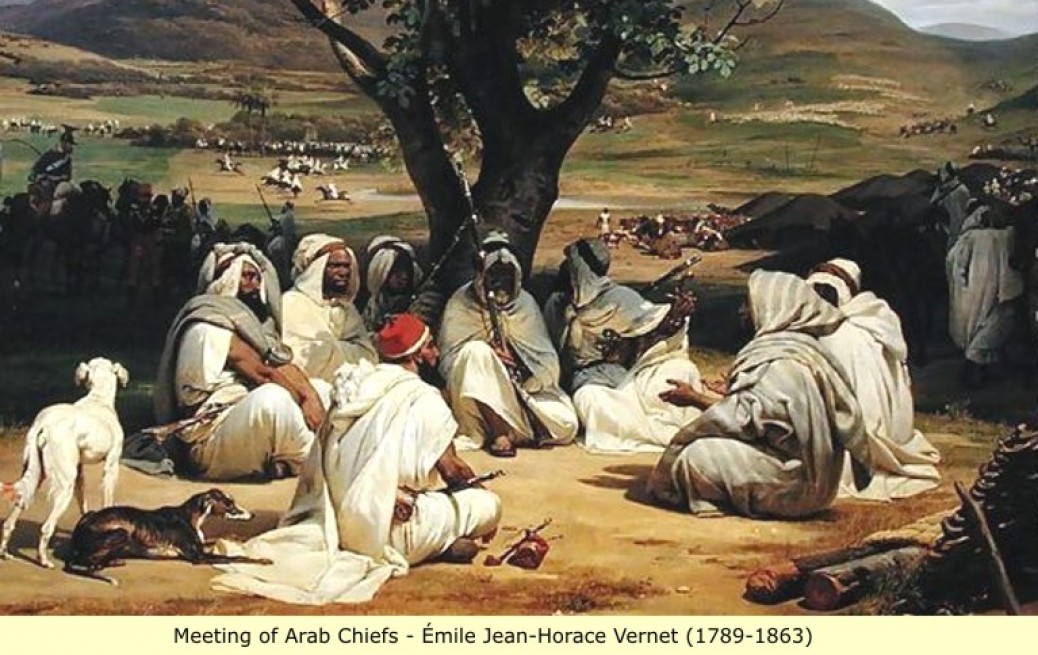

The Arabs are not a distinct ethnic group, since there are both white Arabs and black arabs. Some of the black Sudanese Arabs claim descent ln the male line from Arabs of Mohammed’s time, and may well be correct in their claim. Nor is language a sufficient criterion of Arabness since there are many Arabic-speaking jews who are not normally called Arabs. The figure of a hundred million come from the populations of the states in the Arab League. For membership ln the Arab League the primary criterion appears to be language: but, despite the presence of Lebanon, which is half Christian, this tends to be coupled with the acceptance of Arab-Islamic culture.

Modern Arab intellectuals are well aware of the difficulty in defining an Arab. As long ago as December, 1938, a conference of Arab students in Europe, held in Brussels, declared that “all who are Arab in their language, culture and loyalty (or “national feeling”) are Arabs.” Some of the same intellectuals, however, have spoken of the present disunity of the Arabs as the result of European imperialism during the last century or more. It does not take much knowledge of history to demonstrate that is a complete misconception.

Cultural unity

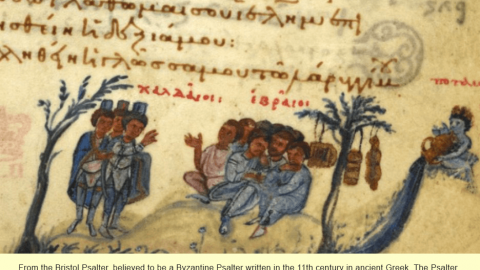

The only time Arabs have been politically united was from about A. D. 634 to 750. Before the Prophet Muhammad – Sallalahu Alayhi Wa Alihi Wa Salam – they were divided into feuding tribes, and not all the tribes entered into alliance with him. The so-called wars of the Apostasy that followed his death ended in unity under the second caliph, and this unity continued until about 750, with the Arabs as a ruling elite in an empire stretching from Spain to the Punjab and Central Asia. Soon after 750, however, the Arabs of Spain formed an independent government and in the following centuries other dynasties gained varying degrees of autonomy. lt often happened that two rulers, both nominally owing their appointment to the politically powerless caliph (or emperor), would fight bitterly to extend their territories at the other’s expense. Where there was an opportunity, the local Muslim princelings were ready to ally themselves with a Christian princeling against Muslim rival: this happened both in Spain and in the Crusading period in Syria. So much for the myth of political unity.

At the same time, there was always an impressive cultural unity. Even before prophet Muhammad -sallalahu alayhi wa alihi wa salam – there was some common cultural awareness among the Arabs. The very word Arab has the connotation of “people who speak clearly.” and is contrasted with ajam, or “people who speak indistinctly.” Though ajam came to be used specially of Persians, the contrast is similar to that between Greeks and “barbarians.” Arabic literature was vigorously cultivated in Spain under Muslim rule. Most rulers and courtiers could write tolerable arabic verse, and a few achieved true elegance. One or two scholars knew by heart vast amounts of the poetry of the leading authors of Syria and Baghdad and the poetical standards of the heartlands still guided taste in Andalusia. At different times several local poets were dubbed “the Mutanabbi of the West.” In much the same way, one called a man “the Milton of America.”

Ottoman influence

Outstanding works from Baghdad quickly made their way to Spain and were studied and commented on. Indeed, in various ways the Arabs of Spain were more Arab than those of the heartlands, perhaps because of their relative isolation in a somewhat alien environment. While one may emphasize the distinctive Iberian character of the Arab literature of Spain, the Arabic language used in Spain remains very close to the classical models. Thus Arab culture has been a potent unifying force even in the face of great political disunity.

The beginning of the twentieth century saw many of the Arab countries nominally parts of the Ottoman Empire: that is, they were under non Arab Muslim rule. This was officially the case with Egypt, although de facto Egypt was being ruled by Britain, as was also the “Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.” Algeria was ruled by the French, who also had some say in Morocco and Tunisia. World War I freed the Arabs from the Ottoman Empire, but brought many of them varying degrees of European tutelage. Only in the early 1950’s did most of the Arabs become completely independent. Through this whole period, however, there has been no significant progress toward political union. As long as the Arabs were under foreign occupation it was easy for them to claim that only imperialism divided them, that their separate “national struggles” were in fact common cause and that union would be easily achieved once the foreigners were ousted. Some twenty years of independence have given the lie to this hope.

The Contemporary conundrum

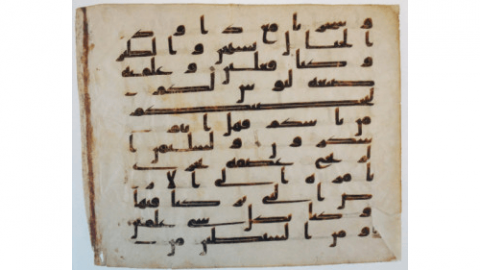

The League of Arab States was founded in 1945 by Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria. Transjordan and Yemen. It has since grown to include Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, the Sudan, and various smaller states like Kuwait. Its aim, however, has never been unity but only cooperation, and even this limited goal has sometimes proved very difficult in the political field. The chief successes of the League have probably been in cultural matters, such as the formation of a library including microfilms of rare manuscripts.

There have been numerous more specific proposals for union, but these have now been forgotten or have turned sour. Egypt has been involved in a number of such projects: the unity of the Nile Valley (with the Sudan), the United Arab Republic (with Syria, which function for a short time and then was dissolved), federation with Yemen, and a union with Libya. Then there have been projects of a Greater Syria and a union of the Fertile Crescent (Syria an Iraq). None of these has worked in practice. While some Arabs have pushed idealistic proposals for unity, others seem determined to press their quarrels, both old and new. There was deep-rooted dynastic rivalry between the family ruling Saudi Arabia and the Hashemite family of Jordan and Iraq. Morocco and Algeria have yet to agree on the border between them (an important factor in Hassan’s attempted nonviolent march into the Spanish Sahara in November, 1975). Iraq, in its greed for oil, threatened Kuwait. During the civil war in the Yemen, Egypt backed the republicans and Saudi Arabia the monarchists. And of course, Gamai Abdai Nasser of Egypt quarreled with Qasim of Iraq over who should be the leader of the Arabs.

Along with all this, however, strong cultural affinities have persisted throughout the Arab world. A literary movement in one country quickly spreads to the others. Around 1930, for example, similar “romantic” features were to be seen in the poetry of Syrian exiles in America, of the Egyptian “Apollo” group, and of the Tunisian ash-Shabbi, the last having been born in an oasis of the interior. Similarly, the “free verse” movement, which appeared in Iraq in 1949, has spread as far as Morocco. Nor is the sense of cultural affinity restricted to intellectuals. The Algerian man in the street clearly has a stronger feeling of Kinship with the Asian fellow-Arab of Iraq than with the non- Arab fellow-African of Mali.

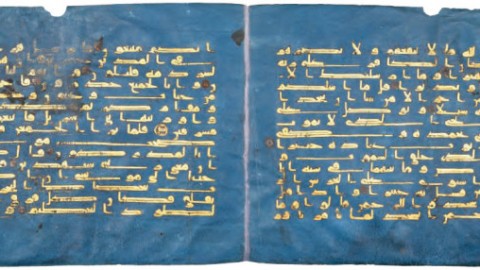

This long story of political disunity and cultural affinity is not the end of the matter. There are other forces at work beneath the surface, and we may today be witnessing a shift of emphasis that could, over time, prove crucial. The crucial Question is that of religion. For many centuries the basis of cultural affinity has been primarily religious. The religion of Islam provided the historical impetus creating the vast society to which the Arabs belonged. Intellectual disciplines associated with religion were the flywheel that maintained a steady, even movement. Within the community of Muslims, however, there was the still stronger bond of the Arabic Language. Arabic had a special status as the language of revelation. Arabic linguistic and literary standards remained remarkably homogeneous in the various regions of the Arab world and even in other Islamic provinces. This is the way it has been for centuries.

References

Editor’s Note: 1In a era dominated by Entertainment and Confusion, Distinguishing clearly between authentic Christianity taught by the 12 Apostles and roman consecrated Paulinism of mithraist origin is crucial.

François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette (1821 – 1881) French scholar, Archaeologist, Egyptologist, and the founder of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

“OUTLINES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN HISTORY”

TRANSLATED AND EDITED, WITH NOTES, BY MARY BRODRICK

With, an Introductory Note by William C. Winslow, D.D., D.C.L.

LL.D., Vice-President of the Egypt Exploration Fund for the United States

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS, NEW YORK, 1892

Page 28

Quote:

“How often do we see in Eastern monarchies and even in European states a difference of origin between the ruling class, to which the royal family belongs, and the mass of the people! We need not leave Western Asia and Egypt; we find there Turks ruling over nations to the race of which they do not belong, although they have adopted their religion. In the same way as the Turks of Baghdad, who are Finns, now reign over Semites, Turanian kings may have led into Egypt and governed a population of mixed origin where the Semitic element was prevalent. If we consider the mixing up of races which took place in Mesopotamia in remote ages, the invasions which the country had to suffer, the repeated conflicts of which it was the theatre, there is nothing extraordinary that populations coming out of this land should have presented a variety of races and origins.”

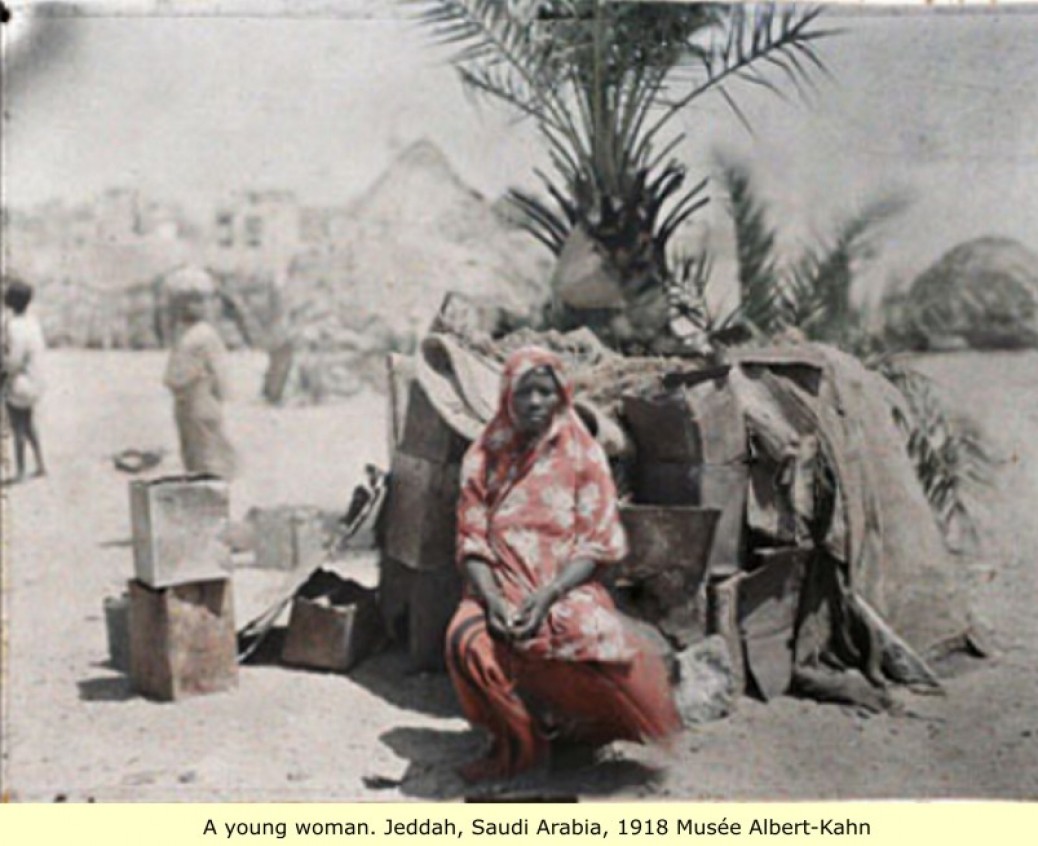

“The inhabitants of this part of Arabia nearly all belong to the race of Himyar. Their complexion is almost as black as the Abyssinians,”– Baron von Maltzan, ‘Geography of Southern Arabia’ (1872)

“ [the Hamida are] small chocolate colored beings, stunted and thin… with mops of bushy hair… straggling beards , vicious eyes, frowning brows … armed with scabbards slung over the shoulder and Janbiyyah daggers…” a people “of the great Hejazi tribe that has kept his blood pure for the last 13 centuries…”– Sir Richard Burton (1879)

“The people of Dhufar are of the Qahtan tribe, the sons of Joktan mentioned in Genesis: they are of Hamitic or African rather than Arab types…”–Arnold Wilson, The Geographical Journal (1927)

“the most prosperous tribe of all the Hamitic group, possessing innumerable camels, herds of cattle and the richest frankincense country. They resemble the Bisharin tribe of the Nubian desert. Men of big bone , they have long faces long narrow jaws, noses of a refined shape long curly hair and brown skin.”–Richmond Palmer (1929)

“Mahra is the Arab name for the Bedouin tribes who are different in appearance to other Arabs, having almost beardless faces, fuzzy hair and dark pigmentation – such as the Qarra, Mahra and Harasis… Also on “…the Qarra, Mahra and Harasis with parts of other tribes. The language is derived from the language of the Sabaeans, Minaeans and Himyarites. The Mahra with other Southern Arabian peoples seem aligned to the Hamitic race of north-east Africa… The Mahra are believed to be descended from the Habasha, who colonized Ethiopia in the first millennium BC”– David Phillips, Peoples on the Move (2001)

“European observers have made much of their physical resemblance to Somalis and Ethiopians, but there is no historical evidence of any connections.”– E. Peterson, ‘Oman’s Diverse Society: Southern Oman’

“Mr. Baldwin draws a marked distinction between the modern Mahomedan Semitic population of Arabia and their great Cushite, Hamite, or Ethiopian predecessors. The former, he says, ‘are comparatively modern in Arabia,’ they have ‘appropriated the reputation of the old race,’ and have unduly occupied the chief attention of modern scholars.”– Charles Hardwick (1872)

“Among ‘these Negroid features which may be counted normal in Arabs are the full,rather everted lips, shortness and width of nose, certain blanks in the bearded areas of the face between the lower lip and chin and on the cheeks; large, luscious,gazelle-like eyes, a dark brown complexion, and a tendency for the hair to grow in ringlets. Often the features of the more Negroid Arabs are derivatives of Dravidian India rather than inheritances of Hamitic Africa. Although the Arab of today is sharply differentiated from the Negro of Africa, yet there must have been a time when both were represented by a single ancestral stock; in no other way can the prevalence of certain Negroid features be accounted for in the natives of Arabia.”– Henry Field, Anthropology Memoirs Volume 4 (1902)

“In Arabia the first inhabitants were probably a dark-skinned, shortish population intermediate, between the African Hamites and the Dravidians of India and forming a single African Asiatic belt with these.”– Handbook of the Territories which form the Theater of Operations of the Iraq Petroleum Company Limited and its Associated Companies